As a drover headed cattle up the Chisholm Trail to the railheads, he had one last stop for rest and supplies: Fort Worth, Texas.

Beyond Fort Worth, he’d be crossing the Red River into Indian Territory.

Between 1866 and 1890, drovers trailed more than four million head of cattle through Fort Worth. The city soon became known as “Cowtown.”

When the railroad arrived in 1876, Fort Worth became a major shipping point for livestock, so the city built the Union Stockyards, two and a half miles north of the Tarrant County Courthouse, in 1887.

But the Union Stockyards Company lacked the funds to buy enough cattle to attract local ranchers, so President Mike C. Hurley invited wealthy Boston capitalist Greenleif Simpson to Fort Worth in hopes he would invest.

A lucky fluke won the Stockyards an investor.

Simpson arrived and found the pens full of cattle; he decided Fort Worth represented a good market, and made plans to invest. Little did he know, the pens didn’t normally hold that much cattle; he’d simply arrived on the heels of heavy rains and a railroad strike.

On April 27, 1893, Simpson bought the Union Stockyards for $133,333.33 and changed the name to the Fort Worth Stockyards Company.

Simpson invited other investors to join him, including his Boston neighbor, Louville V. Niles, whose primary business was meatpacking. They soon realized that instead of shipping the cattle off to other markets to be processed, they’d be much better off building meat packing plants nearby so they could keep the business in the city. The investors began working to attract major packers to Fort Worth, and by about 1900, they had persuaded both Armour & Co. and Swift & Co. to build plants near the Stockyards.

The businessmen planned construction – by coin toss.

Armour and Swift held a coin toss to decide who would get which tract of land. Armour won the toss and chose the northern site; construction began in 1902.

However, Swift & Co. ended up getting the better end of the bargain with the southern site, which contained a large gravel pit that they used for the construction of their plant. They even sold some of the gravel to Armour.

That same year, construction started on the pens, the barns, and the new Livestock Exchange Building, which housed the many livestock commission companies, telegraph offices, railroad offices and other support businesses. It became known as “The Wall Street of the West.”

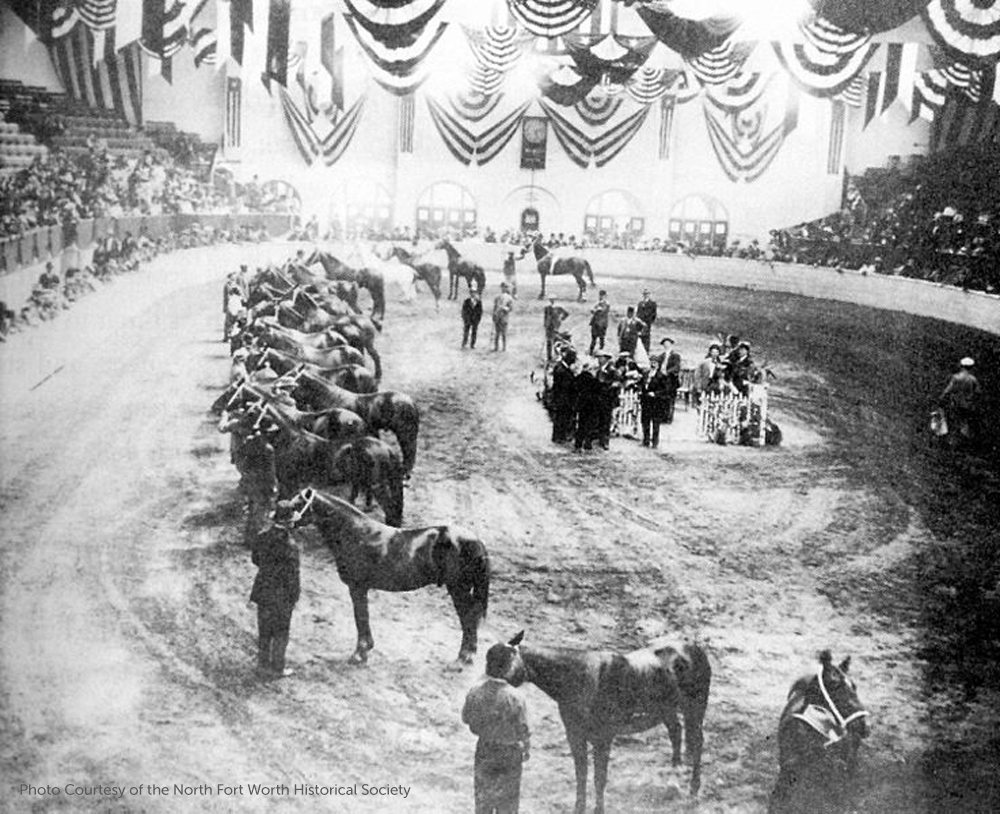

The success of the Stockyards meant the area needed an indoor show facility. In 1907, construction began on a grand coliseum – now known as the Cowtown Coliseum – that was completed in just 88 working days, in time for the grand opening of the Feeders & Breeders Show. The Coliseum became the home of the first indoor rodeo.

After the war, everything changed.

The Stockyards prospered through droughts and floods – they were even rebuilt with new flame-resistant materials after two disastrous fires killed a large number of the penned livestock – but the booming business couldn’t last forever.

During World War II, the Fort Worth Stockyards processed 5,277,496 head of livestock, making 1944 the peak year of the entire operation. Unfortunately, the decline of the Stockyards soon began with the decline of the railroad.

After World War II, newly paved roads gave rise to the trucking industry, with lower costs and greater flexibility than the railroads. This meant the market moved to the shipper instead of the meat packer, and smaller local livestock auctions and feedlots started drawing business away from central locations like the Stockyards.

It was a whole new way to market livestock, as auctions at the Stockyards shrank and all the major packers in the United States struggled to adapt. Both Armour and Swift had huge, outdated plants that now contended with risings costs, wages and administrative expenses. Armour was the first to close his Fort Worth plant in 1962; Swift hung on until 1971.

Armour’s unique office building was demolished, but the classic Swift headquarters building lived on, first as the home of the old Spaghetti Warehouse, a popular restaurant during the 1970s, and now as corporate offices for XTO Energy.

By 1986, Stockyards sales reached an all-time low of 57,181 animals.

The Legacy Lives on.

In 1976, Charlie and Sue McCafferty founded the North Fort Worth Historical Society to preserve Fort Worth's livestock heritage.

This new venture helped establish the Fort Worth Stockyards National Historical District and bring about the restoration of landmarks including the Livestock Exchange Building, the Coliseum and the former Swift & Co. headquarters.

In 1989, the North Fort Worth Historical Society opened the Stockyards Museum in the historic Exchange Building. Today, the museum hosts thousands of visitors from all over the world each year, and is constantly growing its facilities and its collection.

True to its history, the Stockyards still hosts the world’s only twice-daily cattle drive. All this – plus more than a hundred new shopping, dining and entertainment venues – makes the Fort Worth Stockyards National Historical District one of Texas’ most popular tourist destinations.

Day or Night, we invite you as you begin your adventure; where the brick streets welcome you into an authentic western experience.